Nexperia’s Industrial Technology and Engineering Center (ITEC) has a rich history in developing state-of-the-art products and industrial production solutions for the semiconductor domain. But when the group ran into the difficult task of balancing deliverables with its target costs during the development of its cutting-edge ADAT3-XF, senior mechanical designer Theo ter Steeg and the ITEC team turned to the training “Design for manufacturing” to help streamline the design process and get a better overview from the start.

Finding the path to a spot on the leading edge of technology development is certainly no easy feat for any company. But to hold that edge, over the span of decades, is an accomplishment shared by far fewer. However, with a lineage that extends back to NXP and even further to Philips, Nexperia and its Industrial Technology and Engineering Center, more commonly known as ITEC, has held on to such position for more than 30 years – with no plans to relinquish its spot any time soon.

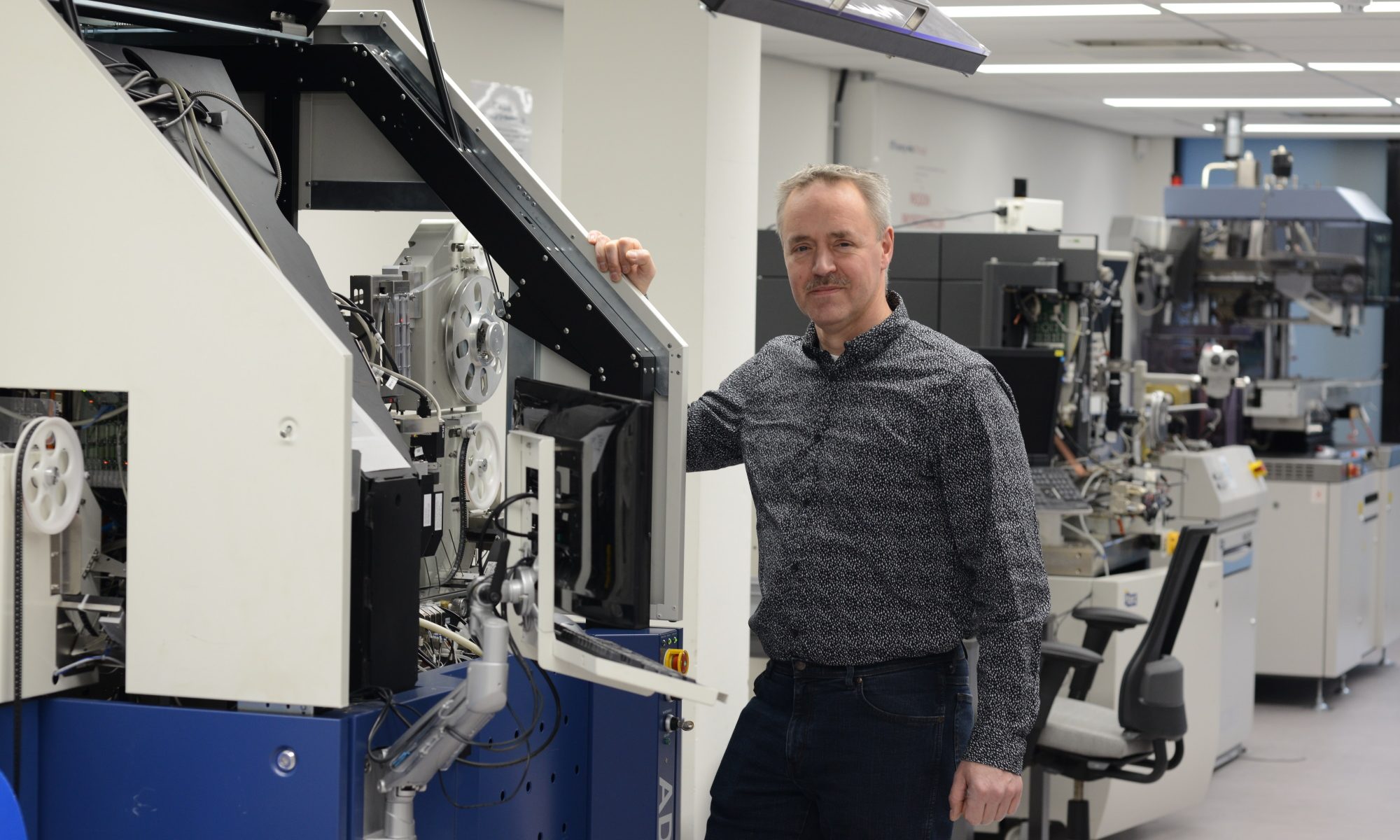

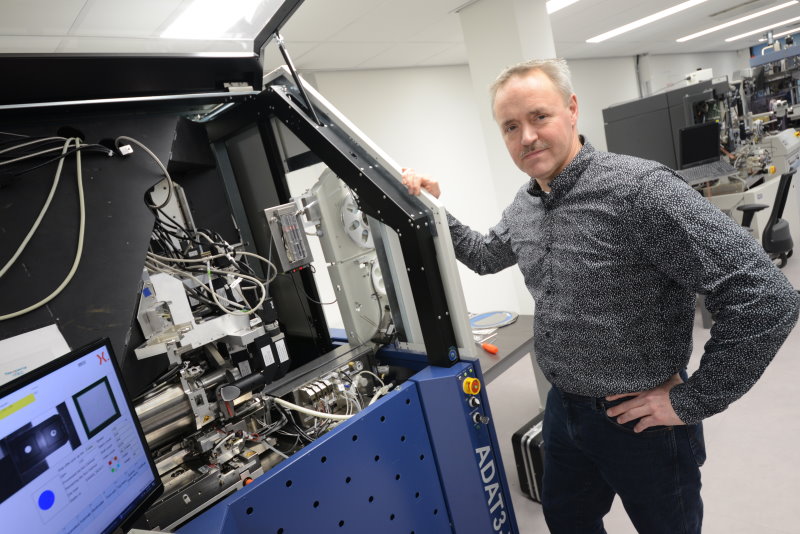

“Since I joined the original ITEC team at Philips in the late 90s, the goal has always been to continue to push the boundaries and improve our offerings,” describes Nexperia senior mechanical designer Theo ter Steeg. Since 2000, he’s dedicated his energy to innovating on one of the company’s featured pick-and-place die-bonding machines, specifically the ADAT3.

“Early on in the development phase of the ADAT3, we already made big steps in improving the speed and accuracy over its predecessor, the ADAT2. Then as the system became more mature, and transitioned from development to the product group, I moved along with it,” recalls Ter Steeg. “Our focus was on the sustainment of the product and creating new features and modules to enhance the entire ADAT3 platform and meet the increasing needs and demands of our customers, specifically in die bonding, die sorting, taping, strip-to-strip glue bonding, flip bonding and more.”

Targets

Meeting these customer demands and working on a continuous innovation cycle, however, also comes with a steep price, both literally and figuratively. As the group poured energy and resources into the project, it found that the established cost targets were often in direct competition with what it aimed to deliver – sending the project a little off the rails. Something had to give, a fact that became abundantly clear while designing the die-bonder strip glue module for the ADAT3-XF platform.

“We always know that the targets for our deliverables are going to be tight, in this line of work, that’s almost always the case. But like on any innovation project, we were enthusiastic and convinced we could hit our marks,” suggests Ter Steeg. “What we encountered, though, was that we were setting these targets early in the process, without all the necessary information at hand, which isn’t sustainable. Quickly, it became apparent we were going to miss our targets; the question was by how much.”

Confident that the project could be saved and put back on track, Theo and his team began discussing their options. In his mind, Ter Steeg remembered an article he’d read in Mechatronica&Machinebouw about the “Design for manufacturing and assembly” training from fellow Philips descendant High Tech Institute. Having looked further into the course content and seeing that the key points of the training aligned with the areas he wanted to improve, Ter Steeg reached out to the course instructor Arnold Schout.

Ter Steeg’s particular interest in the Design for manufacturing training was spurred by two specific topics: cost calculations and improvements in determining lead times. “From the first conversation, Schout showed us that he had a clear understanding of our challenges with a clear vision on how we could address them,” says Ter Steeg. “He worked with us to design an in-company edition of the training. Working in tandem, we were able to customize the training to be precisely tailored to our specific needs.”

Eye-opener

To help address ITEC’s cost-calculating needs, Schout worked directly with team members to create an internal detailed spreadsheet that can take into account the cost of various parts and modules within the machine. By linking this to a CAD model of the system, engineers can see precisely how any individual part, motor or module affects the total cost – including material, machine and man-hours.

“This was an eye-opener for us. Normally, we would design something with a rough estimation of what the various parts and components would cost, but as we go forward in the process, we often make on-the-go decisions to improve performance specifications or fulfill function requests from our customers, without knowing exactly how the cost will be affected down the line,” explains Ter Steeg. “And on a machine like this, with more than 8,000 parts, those changes really add up. Of course, we like to make improvements, but at some point, the question must be, at what cost. With this new way of working and the detailed document, we could gain a lot of clarity on this and improve our system and our way of working.”

Similar to the cost calculation form, Schout also helped the ITEC team to design a lead-time document, where the group could again enter detailed information for all of its parts and modules, which would then provide much more precise information on what the expected lead times would be for specific solutions.

“Working with Arnold and High Tech Institute in the ‘Design for manufacturing’ training has really opened the doors to evolving our processes and our continued innovation. Their level of knowledge and ability to guide the training to fit our specific needs have enabled us to work in a much more sophisticated way, with a clearer understanding and better-defined goals throughout the entire manufacturing process,” illustrates Ter Steeg. “While we only recently just finished this training and perhaps it’s still a bit too early to say definitively, we can already see many of the benefits we hoped to gain.”

This article is written by Collin Arocho, tech editor of Bits&Chips.