High Tech Institute trainer Cees Michielsen highlights a handful of trends in the field of system requirements engineering. For High Tech Institute, he provides the 2-day training ‘System requirements engineering‘ several times a year.

Can we objectively say that a requirement is of good quality? What would be the measure for good? Is there something like ‘good enough’? Most of the answers to these questions can be found in the work of Philip Crosby, William Edwards Deming and Joseph Juran. These three quality gurus are no longer among us, but their ideas remain a great source of inspiration.

As requirements are the result of a requirements engineering process, it seems logical to check if a requirement meets the goals of the process. Firstly, the stakeholder needs have been established, and secondly, a correct and complete transition of the stakeholder needs is ensured up to the decomposition level where requirements can be implemented into hardware or software components. I will focus here on the second goal.

A distinction is made between intrinsic and extrinsic requirement quality. Intrinsic means that the requirement’s quality is determined by the way it’s documented or presented to the reader – the requirement’s syntax. This can be either purely textual or embellished with images, tables and more. The check can be done, in theory, by persons or applications lacking subject matter knowledge. They don’t need to understand what the requirement is about but rather see if it violates rules for writing requirements. Deming speaks of “pride of workmanship” and “well-crafted requirements.” In the course of the last 10-15 years, software tools to support these quality checks have become more and more advanced. In tools such as QVScribe, checklists like the Writing Requirements guideline of the International Council on Systems Engineering (Incose) are completely embedded and intrinsic quality checks are fully automated (including various requirements templates like EARS and IREB).

Note that the intrinsic quality only covers one-third of the total requirements quality. But the intrinsic quality checks do have value. If they’re carried out and corrections are made before the requirement is reviewed by subject matter experts and relevant stakeholders, these tools can save time and indeed be helpful to improve the quality of requirements.

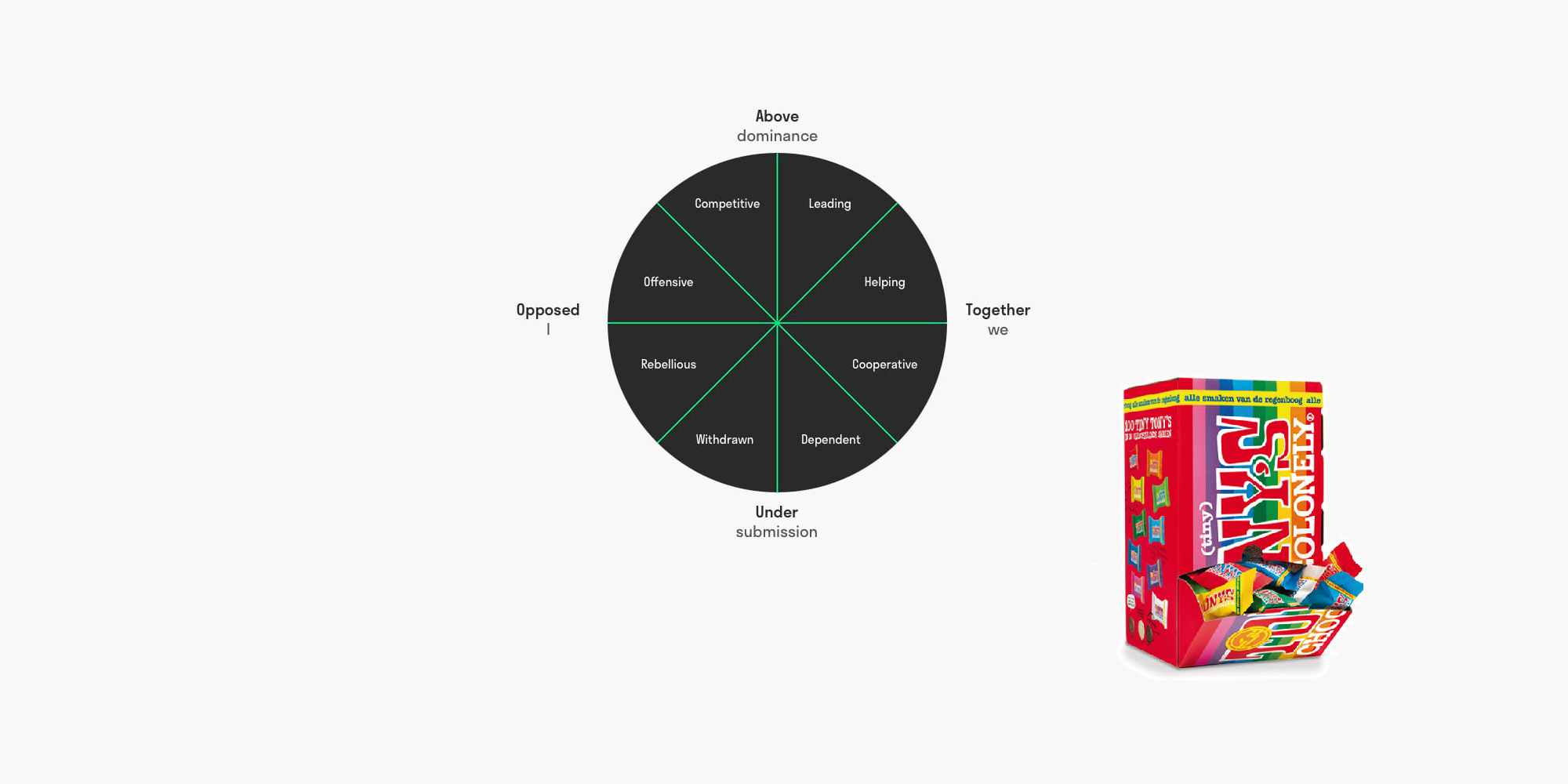

But tools won’t help you determine if your requirement is meaningful to the intended audience. This is where the extrinsic quality of requirements comes in. It applies in two directions: back to the stakeholders who requested a specific feature of the product to be developed or a product characteristic or behavior (the source audience), and forward to the receivers of the requirement (the target audience).

Let’s consider the following requirement: “The responsiveness of the system shall be less than or equal to 0.5 ms.” This requirement will most likely pass the automated quality checks with flying colors. In practice, it’s often formulated as: “System responsiveness: ≤ 0.5 ms.” Would you say these requirements are of equal quality? From a syntactical perspective, the first will give a higher score as it contains a directive, but it isn’t until we ask the relevant stakeholders that we have some idea whether the intended meaning was translated correctly.

[Courseinstructor heading=”‘equirements engineers need to have their requirements checked and judged.'”

Quality is conformance to requirements, says Crosby. Did we, as requirements engineers or business analysts, correctly translate the stakeholder’s need into a system requirement? This can only be answered by the stakeholders who posed the original need. So requirements engineers need to have their requirements checked and judged – an activity that’s perceived as difficult.

Suppose the customer says that the engineer hasn’t understood the request? Or that he completely missed the point? Such feedback isn’t always pleasant and that causes a requirements engineer to avoid these confrontations. He often takes the safe route by contacting someone from the project to represent the customer or stakeholder.

That’s not a smart attitude. We want to make sure we’ve understood the stakeholder’s needs and translated them correctly and completely into requirements. Therefore, there’s no other way than to ask these difficult questions directly.

Quality is fitness for purpose, says Juran. Requirements must contain sufficient information and detail for designers to come up with solutions. The requirements are expected to be quantified to enable testers to verify and validate their successful implementation. In short, they must be clear, unambiguous, meaningful and have sufficient detail for those who receive the requirement as input for their work.

I’ve seen cases where no requirement documentation existed between an OEM and one of its component suppliers. Just a verbal agreement. Although this may seem an unacceptable situation in some cultures, the goals of the requirements engineering process were met. The supplier has been delivering the component with constant quality to the satisfaction of the customer for over twelve years now.

What would you do in situations like these? How do you see the quality of requirements in your company? How would you handle stakeholder needs like “I want the next version of the car to be more energy-efficient”? I’d be happy to hear from you, to learn and pass it on.