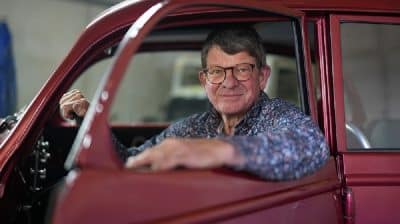

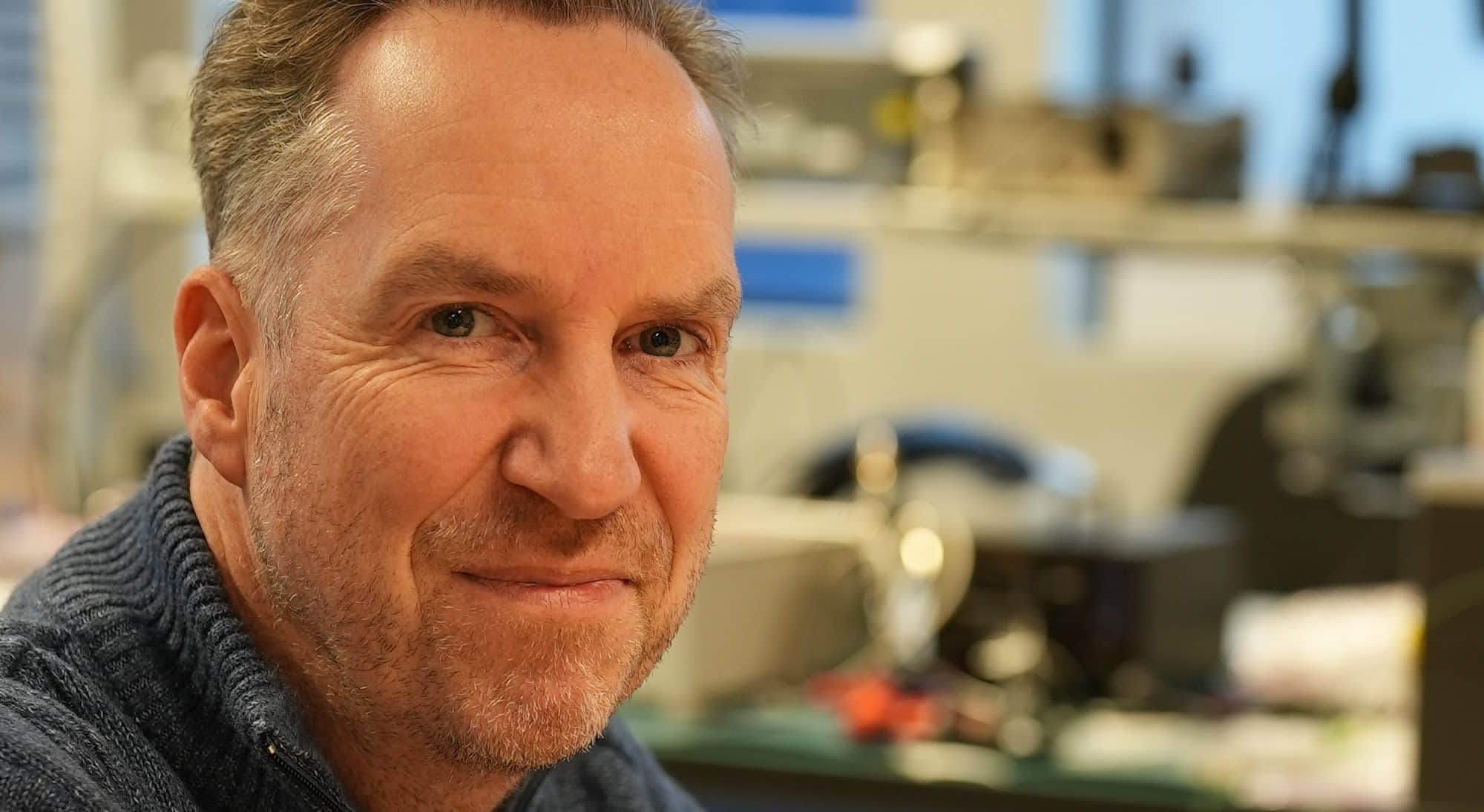

Erik Manders and Marc Vermeulen take on a leading role in the training “Design Principles for Precision Engineering” (DPPE). The duo takes over from Huub Janssen, who was the face of the training for seven years. Part two of a two-part series: training, trends, and trainers.

When it comes to knowledge sharing within the Eindhoven region, the “Design Principles for Precision Engineering” (DPPE) training is considered one of the crown jewels. The course originated in the 1980s within the Philips Center for Manufacturing Technology (CFT), where the renowned professor Wim van der Hoek laid the foundation with his construction principles. Figures like Rien Koster, Piet van Rens, Herman Soemers, Nick Rosielle, Dannis Brouwer, and Hans Vermeulen built upon it.

The current DPPE course, offered by Mechatronics Academy (MA) through the High Tech Institute, is supported by multiple experts. The lead figures among them have the special task of keeping an eye on industry trends. “Our lead figures signal trends, new topics, and best practices in precision technology,” says Adrian Rankers, a partner at Mechatronics Academy responsible for the DPPE training.

When asked about his ‘fingerprints’ on the DPPE training, Janssen refers to his great inspiration, Wim van der Hoek. “I’m not a lecturer nor a professor with long stories. I like to lay down a case, work on it together, and then discuss it. With Van der Hoek, we would sit around a large white sheet of paper, and then the problems would be laid on the table.”

Virtual Play

Janssen says that as a lead figure, he was able to shape the DPPE training. He chose to give participants more practical assignments and discuss those cases in class. Rankers: “Right from the first morning. After we explain the concept of virtual play, we ask participants to start working with it.” Janssen: “Everyone thinks after our explanation: I’ve got it. But when they put the first sketches on paper, it turns out it’s not that simple. That’s the point: because when they do the calculations themselves, it really sticks.”

On the last day of the training, participants are tasked with designing an optical microscope in groups of four. Janssen: “They receive the specifications: the positioning table with a stroke of several millimeters, a specific resolution, stability within a tenth of a micrometer in one minute, etc. Everything covered in this case has been discussed in the days prior: plasticity, friction, thermal center, and more.”

Vermeulen: “The fun part is that people must work together, otherwise, they won’t make it.”

Janssen: “We push four tables together, and they really have to work the four of them as a team. Then you see some people reaching for super-stable Zerodur or electromagnetic guidance or an air bearing, and someone else says: ‘Also consider the cost aspect.’”

Not Easy

Participants experience the difficulty level very differently, regardless of their educational background, Janssen observes: “It depends on their prior knowledge, but it’s challenging for everyone. People are almost always highly educated, but when they need to come up with a design, they often don’t know whether to approach it from the left or right.”

However, he believes it’s not rocket science. “It’s not complex. It’s about calculations that you should be able to do in five minutes on a beer mat.”

All four of them agree that it’s about getting a feel for the material. “You should also be able to quantify it, quickly calculate it,” emphasizes Vermeulen.

Janssen offers a simple thought experiment: “Take two rubber bands. Hold them parallel and pull them. Then knot them in series and pull again. What’s the difference? What happens? Where do you have to pull hardest to stretch them a few centimeters? Not everyone has an intuitive grasp of that.”

Rankers: “It’s a combination of creativity and analytical ability. You have to come up with something, then do some rough calculations to see how it works out. Some people approach it analytically, others can construct wonderfully. They may not know exactly why it works, but they have a great feel for it.”

Calculation Tools

Creativity and design intuition cannot be replaced by calculation tools, they all agree. “You can let a computer do the calculations,” says Janssen, “but then you still have to assess it. What if it’s not right? There are thousands of parameters you can tweak. It’s about feeling for construction, knowing where the pain points are. You don’t need a calculation program for that.”

Manders: “We talk about the proverbial beer mat because you want to make an initial sketch or calculation in a few minutes. If you let a computer calculate, you’re busy for days. Building an initial model takes a long time. But a good constructor can put that calculation on paper in a few minutes. If afterwards you are busy for an hour, you have a good sense of which direction it’s going. I think that’s the core of the construction principle course: simple calculations, not too complicated, choose a direction, and see where it goes.”

White Sheet of Paper

Manders observes that highly analytical people are often afraid to put the first lines on a blank sheet of paper. To start with a concept. “Often, they are so focused on the details that they get stuck immediately. Creatives start drawing and see where it goes.”

For Manders, training is a way to stay connected with the field of construction. “In my career, I’ve expanded into more areas, also towards mechatronics. But my anchor point is precision mechanics. By training, I can deepen my knowledge and tell people about the basics. It sharpens me as well. Explaining construction principles in slightly different ways helps me in my coaching job.”

He often learns new things during training. “Then I get questions that make me really think. If it’s really tough, I’ll come back to it outside the course. I’ll puzzle it out at home and prepare a backup slide for the next time.”

Vermeulen says he gets a lot of satisfaction from training a new generation of technicians. “That gives me energy. For the current growth in high-tech, it’s also necessary to share knowledge. That applies to ASML, but also to VDL and other suppliers. If we don’t pass on our knowledge, we’ll all hit a wall.”

Complacency

Janssen observes that a certain bias or complacency is common among designers. “When there are many ASML participants in the class, they immediately pull out a magnetic bearing when we ask for frictionless movement. But in some cases, an air bearing or two rollers will do. I’m exaggerating, but designers sometimes have a bias because of their own experience or work environment. With every design question, they really need to go back to the basics, feet on the ground, and start simple.”

Vermeulen: “The simplest solution is usually the best. Many designers aren’t trained that way. I often see copying behavior. But the design choice they see their neighbor make is not necessarily the best solution for their own problem. You could perfectly fine use a steel plate instead of a complex leaf spring. It works both ways, but if you choose the expensive option, you better have a good reason.”

Quarter

“It’s always fun to see how Marc starts,” says Rankers about Vermeulen’s approach in training. “When he talks about air bearings, he asks participants if they use them, what their biggest challenge is, where they run into problems. In a quarter of an hour, he explores the topic and knows what’s familiar to them. Who knows a lot, who knows nothing, or who will be working with it in a project soon.”

Vermeulen: “In my preview, I go over the entire material without diving deep into it. That process gives me energy. In fact, the whole class is motivated, but the challenge is to really engage them at the start. You don’t know each other yet. But I want to be able to read them, so to speak, to get them involved. They need to be eager, on the edge of their seats.”

So it’s not about the slides, Vermeulen emphasizes once again. “It’s about participants coming with their own questions. They all have certain things in mind and are wondering how to make it work.” That’s the reason for the extensive round of questions at the start. “I ask about the different themes they’re encountering. Then I use that as a framework. When a slide about a topic they mentioned comes up, I go into it a bit. That makes it much easier for them to follow. They stay focused.”

Basic Training

DPPE is a basic training. Manders and Vermeulen don’t expect major changes in the material covered, though they see opportunities to bring the content more up to date.

However, participants must still learn fundamental knowledge and principles. Janssen on stiffness, play, and friction—the topics he teaches: “I spend a day and a half on those, but they’re three crucial things. If you don’t grasp these, you’ll never be a good designer. That’s the foundation.” Concepts like passive damping come up briefly, but that’s a complex topic. No wonder Mechatronics Academy offers a separate three-day training for that.

The “degrees of freedom” topic that Manders teaches is another fundamental element. “That just takes some time. You have to go through it,” says Manders.

Vermeulen: “Then comes the translation to hardware. Once participants are familiar with spark erosion, they need to have the creativity to turn to cheaper solutions in some cases. We could emphasize the critical assessment of production method costs more. If you get a degree of freedom in one system with spark erosion, you shouldn’t automatically reach for this expensive production method next time. We could delve more into that translation to hardware. It’s also good to strive for simplicity there.”

Overdetermined

By the way, Wim van der Hoek also looked critically at costs. Rankers: “A great statement from him was that many costs in assembly are caused by things being overdetermined.”

The terms “determined” or “overdetermined” in precision construction essentially refer to this: A rigid body has six degrees of freedom (3 translations and 3 rotations) that fully define its position and orientation. If you want to move that object in one direction using an actuator, you need to fix the other degrees of freedom with a roller bearing, air bearing, or leaf spring configuration.

If you as a designer choose a configuration of constraints that fixes more than five degrees of freedom, the constraints may interfere with each other. Rankers: “That’s called statically overdetermined, and you might get lucky if it works, as long as everything is neatly aligned. The people doing that have ‘golden hands,’ as Wim van der Hoek put it. But the neat alignment can’t change, like with thermal expansion differences.” Especially the gradients and differences in expansion of various components play a big role.

Rankers: “Of course, it’s impossible to perfectly align everything. It also changes over time during use. So internal forces arise within the object you wanted to hold or position due to the ‘fighting’ between the constraints. If that object is a delicate piece of optics that must not deform, you’ve got a big problem. That means you need to avoid overdetermination in ultra-precision machines.”

Vermeulen: “So if you design it to be better determined, it’s easier to assemble, and that gives you a bridge to costs.”

Rankers also notes that the cost aspect should receive more attention than before. He thinks guest speakers could enrich the training with practical examples. Showing examples of affordable and expensive versions. Vermeulen immediately offers an example where you need to guide a lens. “If you make a normal linear guide, the lens sinks a little on the nanometer scale. You can compensate with a second guide, but then the solution might be twice as expensive and twice as complex. Is that really necessary? So as a designer, you can challenge the optics engineer: ‘You want to make it perfect, but that comes at a high cost. We need to pay attention to these things.’”

This article is written by René Raaijmakers, tech editor of Bits&Chips.