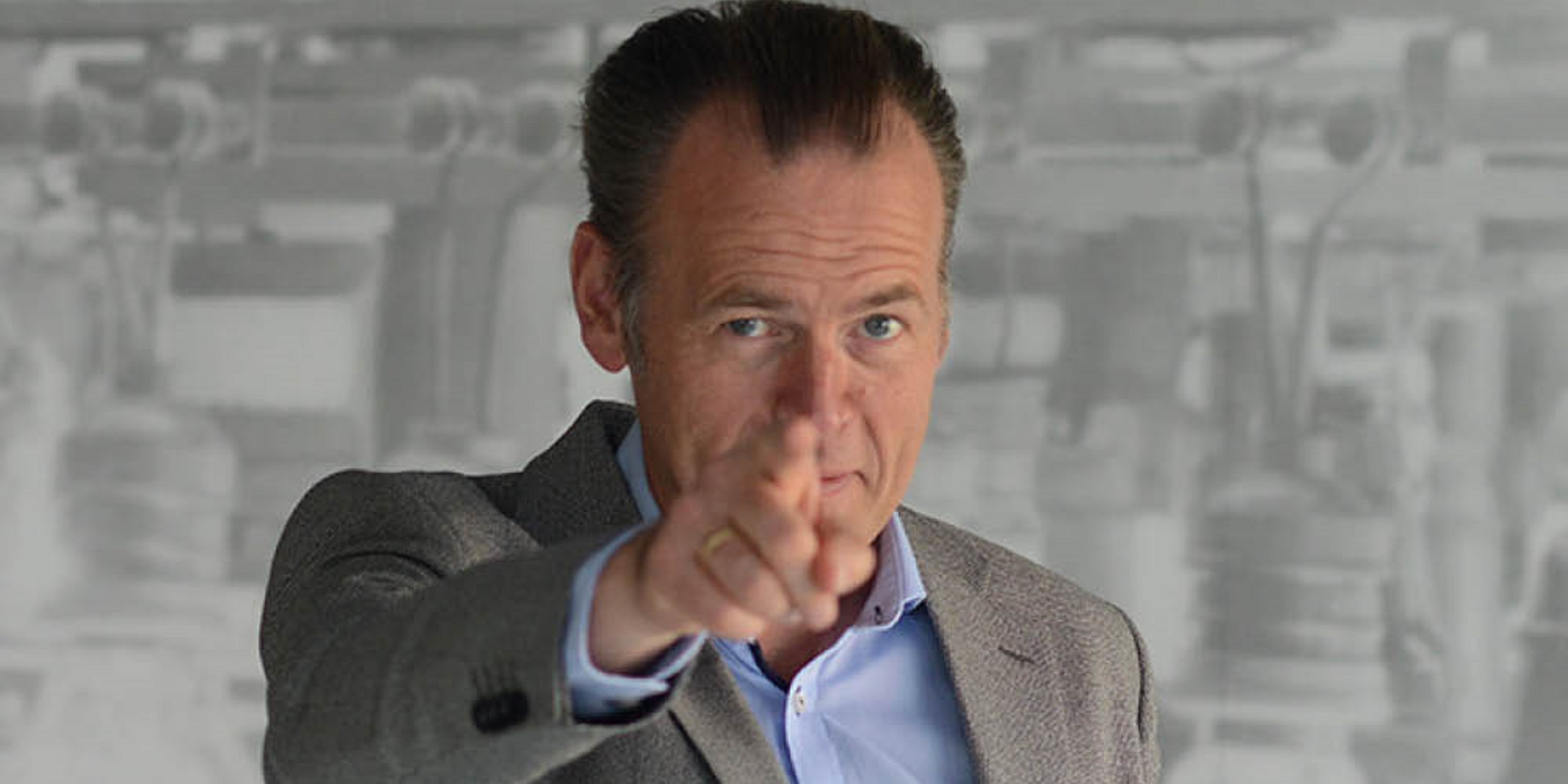

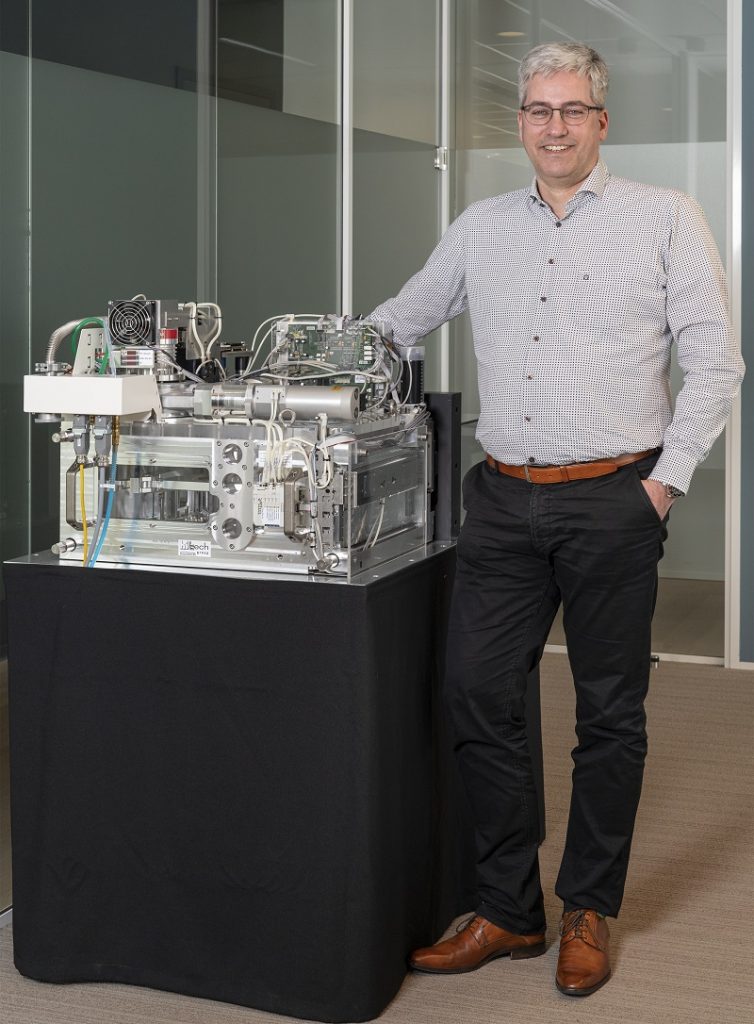

Translating academic insights in the field of mechatronics into industrial practice: that is the core of the training offered by Mechatronics Academy. Adrian Rankers, in addition to Jan van Eijk and Maarten Steinbuch co-founder of this training institute, knows what is going on in the field. He is committed to guaranteeing the best trainers, furthering the development of existing training courses and the setting up of new ones.

“The fact that I ended up in the coaching profession is actually quite logical in retrospect, because education has always attracted me,” says Adrian Rankers. “I gave tutoring as early as the age of fifteen. A few hours at first, but soon, that became more. I remember giving tutoring to the son of a top executive at Shell and quickly becoming his complete homework support. My attraction to the technical side certainly had something to do with my father. He had also studied mechanical engineering and worked, first in industry and later as a professor.”

“It is essential to realize that the students still have to go through the learning curve and that some things are quite difficult and might not be obvious to everyone. As a trainer you have to be aware of this and take the time to do so.”

After completing his mechanical engineering studies at Delft University of Technology, Rankers started his career at Philips at the Centre for Manufacturing Technology (CFT). Here he was involved in the dynamics and control techniques for CD players and wafer steppers. In the evening hours, he worked on his PhD research resulting from this work. Parts of this research were later included in the book The design of high-performance mechatronics by Rob Munnig Schmidt, Jan van Eijk, Georg Schitter and Rankers himself. In addition to the development and consultancy work and his role as group leader, he became involved in the development of mechatronics education for Philips’ own employees, initiated by Jan van Eijk. He also joined the board of the Dutch Society for Precision Engineering (DSPE) in 2008, of which he is still a member today.

Mechatronics Academy

Although he enjoyed working there in engineering and technical management, Rankers made the switch to entrepreneurship in 2010 after twenty-five years of loyal service at Philips. He wanted to focus mainly on transferring his mechatronics knowledge. This eventually led to the idea to set up the Mechatronics Academy together with Jan van Eijk and Maarten Steinbuch. It turned out that there was a need for this: the organization can now rely on sixty to seventy trainers with an industrial background in the field. Mechatronics Academy now provides training courses for around four hundred students per year. These are both open training courses and in-company training courses, specially tailored to companies.

'I like to pass on my knowledge of mechatronics to others.'

“What appeals to me in the field of mechatronics? It is always a multidisciplinary challenge where you work with people from different disciplines. Mechatronics always gives you the opportunity to immerse yourself in all kinds of things. In addition, I like to pass on my knowledge of mechatronics to others,” says Rankers enthusiastically. “In doing so, it is essential to realize that the students still have to go through the learning curve that you yourself have gone through over a number of years and that some things are quite difficult and might not be obvious to everyone. As a trainer you have to have an eye for that and take your time. In accordance with the old saying by Confucius, ‘I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand,’ we work a lot with exercises in small teams. You see how students struggle to put the theory they have just learned into practice and to master the subject matter, but it is precisely this struggle that is an important part of learning. If I can guide them through this, so that they eventually understand it for themselves, it gives me a lot of satisfaction.”

The trainings that Mechatronics Academy organizes are well-attended and get good reviews from the participants. But that certainly doesn’t mean you can rest on your laurels, Rankers believes. “We think it’s important to keep our portfolio up to scratch, to expand and to ensure continuity.”

'Assignments are indispensable for understanding.'

That’s why at Mechatronics Academy they are constantly working to keep the team of trainers up to strength. Good trainers who quit, because they come of age, are replaced with a new generation. To this end, they approach the best content experts in the field, whom they know from their extensive network. They also ensure that they continually adapt existing training courses to the latest academic insights and technological developments. “We adapt existing modules and develop new ones. In addition, we invest a lot in resources that we use during the practical parts of the training courses. Practical assignments, such as working on constellations or carrying out simulations, form an essential part. These assignments are indispensable for understanding,” Ranker describes.

Mechatronics Academy offers its trainings through High Tech Institute

New courses

In addition to keeping existing training courses up to date, Mechatronics Academy also develops new training courses that arise from a need in the market. Ideas for this come from Rankers, Van Eijk and Steinbuch themselves, but also from their trainers. At DSPE meetings or conferences in the field, everyone sticks out their feelers to know what is going on and where needs lie.

Through these practices, beautiful new training courses are created time and time again. For example, the training “Passive damping for high tech systems,” which started last year and has now run twice. In ultra-precise motion systems, dynamics – both loose and in interaction with control technology – play an important role. That is why in today’s practice, and therefore also in the various courses, much attention is paid to the realization of high eigenfrequencies in mechanics. Understanding mode shapes and the extent to which they can be excited by the actuator or perceived by the sensor is also important here. This approach is and remains essential. But with increasing accuracy requirements, this is no longer always sufficient. You then run into the limit of what is physically feasible. The deliberate addition of passive damping then offers extra solution space and becomes a decisive parameter in achieving extreme specifications.

The new training, which focuses on proven ways to achieve passive damping, is very successful, according to Rankers. It is a highly relevant theme in the precision engineering community. Hans Vermeulen, Kees Verbaan and Stan van der Meulen are the trainers. They have an enormous amount of knowledge of the field. The positive response to the training sessions is also reflected in the reactions of participants: “Excellent training,” “Excellent trainers” and “Very inspiring,” to name a few. “There is even interest in this training from abroad,” reports Rankers proudly.

Then there are a number of new training courses in development. From the training “Actuation and power electronics,” which focuses mainly on electromechanical propulsion, the idea arose to set up a training course specifically for piezo materials and their applications. There are also plans to set up a training course “Active thermal control.” Rankers: “How can you keep the temperature and deformations caused by heat sources manageable in a setup? Which control techniques can be used for this? What are suitable sensors for measuring temperatures and deformations with high precision? And which elements can be used for cooling or heating? These are all questions that will be addressed. The training course ‘Thermal effects in mechatronic systems’ has already briefly addressed this, but it is such an important theme in the world of ultra-precision that a separate training course would be appropriate here.”

“Our current training ‘Basics and design principles for ultra-clean vacuum‘ focuses on molecular contamination and how to prevent it. However, there is also a need for a new training course on ‘Particle contamination’,” continues Rankers. “In this training we will discuss particle contamination in vacuum. Unlike molecular contamination – for example by gas molecules trapped in a blind hole of a part placed in vacuum, which leak through the thread to the ultraclean vacuum – these are small pieces of material. These may be, for example, particles loosened by friction between moving parts of the device placed in vacuum. The knowledge from various studies that are already running in this area could serve as a guideline for this.”

'We continue to invest in support material for our training couses, to link the covered theory to industrial practice.'

“Together with our trainers, we are constantly working to improve training, set up new training courses and keep our pool of trainers up to standard,” Rankers summarizes. “We also continue to invest in support material for our training courses, so that we can link the theory we cover directly to industrial practice. This is where our strength lies: translating academic insights into industrial practice, so that trainees can directly deploy their knowledge in our high-tech industry. This is how we continue to keep our training package up-to-date and deliver the best trainers, so that we can continue to live up to the designation ‘excellent training’.”

This article is written by Antoinette Brugman, tech editor of High-Tech Systems.

In the training ‘Object-oriented analysis and design’ participants draw their designs out of hand. Trainer Martijn Ceelen even still likes to use overheadsheets for that.

In the training ‘Object-oriented analysis and design’ participants draw their designs out of hand. Trainer Martijn Ceelen even still likes to use overheadsheets for that.